Battle Of Palmito Ranch Date

The Battle of Palmito Ranch, also known as the Battle of Palmito Hill, is considered past some criteria as the final battle of the American Ceremonious War. Information technology was fought May 12 and 13, 1865, on the banks of the Rio Grande eastward of Brownsville, Texas, and a few miles from the seaport of Los Brazos de Santiago, at the southern tip of Texas. The battle took place more than a month after the general surrender of Confederate forces to Matrimony forces at Appomattox Court House, which had since been communicated to both commanders at Palmito, and in the intervening weeks the Confederacy had collapsed entirely, so information technology could as well exist classified as a postwar action.

Wedlock and Confederate forces in southern Texas had been observing an unofficial truce since the get-go of 1865, just Matrimony Colonel Theodore H. Barrett, newly assigned to control an all-black unit of measurement and never having been involved in combat, ordered an attack on a Confederate camp near Fort Chocolate-brown for unknown reasons. The Union attackers captured a few prisoners, only the following day the assail was repulsed near Palmito Ranch by Colonel John Salmon Ford, and the battle resulted in a Confederate victory. Spousal relationship forces were surprised by artillery said to have been supplied by the French Ground forces garrison occupying the up-river Mexican boondocks of Matamoros.

Casualty estimates are not dependable, simply Union Private John J. Williams of the 34th Indiana Infantry Regiment is believed to have been the final human killed during the engagement. He could then arguably be reckoned equally the concluding man killed in the war.

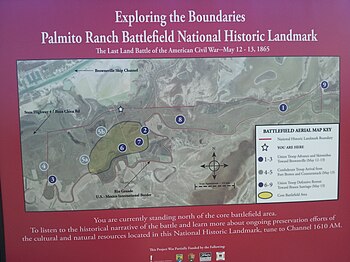

Marker on Texas Throughway iv

Background [edit]

Afterward July 27, 1864, the Union Army withdrew most of the six,500 troops deployed to the lower Rio Grande Valley, including Brownsville, which they had occupied since November 2, 1863. The Confederates were determined to protect their remaining ports, which were essential for cotton sales to Europe and the importation of supplies. The Mexicans across the border tended to side with the Confederates because of the lucrative cotton wool export trade.[ane] Beginning in early 1865, the rival armies in south Texas honored a gentlemen's agreement, as they saw no point in further hostilities between them.[2]

Union Major Full general Lew Wallace proposed a negotiated end of hostilities in Texas to Confederate Brigadier General James E. Slaughter, and met with Slaughter and his subordinate Colonel Ford at Port Isabel on March eleven–12, 1865.[three] Despite Slaughter's and Ford'southward agreement that combat would prove tragic, Slaughter's superior, Confederate Maj. Gen. John Grand. Walker, rejected the ceasefire in a scathing exchange of letters with Wallace. Despite this, both sides honored a tacit agreement not to accelerate on the other without prior written notice.

A brigade of 1,900 Wedlock troops allowable by Col. Robert B. Jones of the 34th Indiana Veteran Volunteer Infantry were on blockade duty at the Port of Brazos Santiago at the mouth of the present-day ship aqueduct of the Port of Brownsville. The 400-man 34th Indiana was an experienced regiment that had served in the Vicksburg Entrada and was reorganized in Dec 1863 equally a "Veteran" regiment, equanimous entirely of veterans from several other regiments whose original enlistments had expired. The 34th Indiana deployed to Los Brazos de Santiago on December 22, 1864, replacing the 91st Illinois Volunteer Infantry, which returned to New Orleans. The brigade also included the 87th and 62nd The states Colored Infantry Regiments ("United states of america Colored Troops", or U.S.C.T.) which had a combined strength of about 1,100. Presently afterward Gen. Walker rejected the armistice proposal, Col. Jones resigned from the army to render to Indiana. He was replaced in the regiment by Lt. Col. Robert G. Morrison and at Los Brazos de Santiago by Colonel Theodore H. Barrett, commander of the 62nd U.South.C.T.

The thirty-year-onetime Barrett had been an army officer since 1862, simply he had nevertheless to meet combat. Broken-hearted for college rank, he volunteered for the newly raised "colored" regiments and was appointed in 1863 as colonel of the 1st Missouri Colored Infantry. In March 1864, the regiment became the 62nd UsC.T. Barrett contracted malaria in Louisiana that summertime, and while he was on convalescent go out, the 62nd was posted to Brazos Santiago. He joined information technology there in Feb 1865.

Reasons for fighting [edit]

Historians still debate why this engagement at Palmito Ranch took identify. Lee had surrendered to Grant in Appomattox Court Firm, Virginia, on April 9, triggering a series of formal surrenders in other places throughout the country. The Amalgamated and Matrimony officers in Brownsville besides knew that Lee had surrendered, finer ending the state of war.

Presently after the battle, Barrett'south detractors claimed he desired "a piffling battlefield glory before the war ended altogether."[2] Others have suggested that Barrett needed horses for the 300 unmounted cavalrymen in his brigade and decided to take them from his enemy.[4] Louis J. Schuler, in his 1960 pamphlet "The last battle in the War Between the States, May 13, 1865: Confederate Force of 300 defeats 1,700 Federals about Brownsville, Texas", asserts that Brig. Gen. Egbert B. Dark-brown of the U.S. Volunteers had ordered the expedition to seize equally contraband 2,000 bales of cotton stored in Brownsville and sell them for his ain profit.[5] Merely Brown was not even appointed to command at Brazos Santiago until later in May.[6]

According to historian Jerry Thompson:

- What was at stake was accolade and money. With a stubborn reluctance to admit defeat, Ford asserted that the nobility and manhood of his men had to be defended. Having previously proclaimed that he would never capitulate to "a mongrel strength of Abolitionists, Negroes, plundering Mexicans, and perfidious renegades"...Ford was not about to surrender to invading black troops.... Even more than important was the large quantity of Richard Rex and Mifflin Kenedy's cotton fiber stacked in Brownsville waiting to exist sent across the river to Matamoros. If Ford did not concur off the invading Federal force, the cotton would be confiscated by the Yankees and thousands of dollars lost."[seven]

Battle [edit]

Wedlock Lieutenant Colonel David Branson wanted to attack the Amalgamated encampments commanded by Ford at White and Palmito ranches near Fort Brown outside Brownsville. Branson's Union forces consisted of 250 men of the 62nd UsC.T. in eight companies and two companies of the (U.S.) 2nd Texas Cavalry Battalion. The 300-man second Texas, like the earlier-formed 1st Texas Cavalry Regiment, was equanimous largely of Texans of Mexican origin who remained loyal to the U.s..[8] They moved from Brazos Santiago to the mainland. At first Branson's expedition was successful, capturing iii prisoners and some supplies, although it failed to achieve the desired surprise.[9] During the afternoon, Confederate forces under Helm William North. Robinson counterattacked with less than 100 cavalry, driving Branson back to White's Ranch, where the fighting stopped for the nighttime. Both sides sent for reinforcements; Ford arrived with six French guns and the residual of his cavalry force (for a full of 300 men), while Barrett came with 200 troops of the 34th Indiana in 9 under-force companies.[ten] [xi]

The side by side day, Barrett started advancing westward, passing a half-mile to the west of Palmito Ranch, with skirmishers from the 34th Indiana deployed in advance.[12] Ford attacked Barrett's forcefulness as information technology was skirmishing with an accelerate Confederate force along the Rio Grande about iv p.m. He sent a couple of companies with artillery to attack the Wedlock right flank and the remainder of his strength into a frontal assail. Afterwards some confusion and tearing fighting, the Union forces retreated toward Boca Chica. Barrett attempted to form a rearguard, merely Confederate artillery prevented him from rallying a force sufficient to exercise and so.[xiii] During the retreat, which lasted until fourteen May, 50 members of the 34th Indiana's rearguard company, 30 stragglers, and 20 of the dismounted cavalry were surrounded in a bend of the Rio Grande and captured.[14] The battle is recorded as a Confederate victory.[fifteen]

Fighting in the battle involved Caucasian, African-American, Hispanic, and Native American troops. Reports of shots from the Mexican side, the sounding of a warning to the Confederates of the Union approach, the crossing of Regal cavalry into Texas, and the participation by several among Ford'south troops are unverified, despite many witnesses reporting shooting from the Mexican shore.[12]

In Barrett's official report of August 10, 1865, he reported 115 Spousal relationship casualties: 1 killed, 9 wounded, and 105 captured.[16] Confederate casualties were reported as v or six wounded, with none killed.[17] Historian and Ford biographer Stephen B. Oates, however, concludes that Union deaths were much college, probably around 30, many of whom drowned in the Rio Grande or were attacked by French border guards on the Mexican side. He likewise estimated Amalgamated casualties at approximately the aforementioned number.[five] [xviii]

Using court-martial testimony and post returns from Brazos Santiago, historian Jerry D. Thompson of Texas A&M International University determined that:

- the 62nd U.S.C.T. incurred 2 killed and 4 wounded;

- the 34th Indiana had ane killed, one wounded, and 79 captured; and

- the 2nd Texas Cavalry Battalion had one killed, seven wounded, and 22 captured,

- totaling four killed, 12 wounded, and 101 captured.[xix]

Individual John J. Williams[twenty] of the 34th Indiana was the concluding fatality during the Boxing at Palmito Ranch, likely making him the final combat death of the entire state of war.[21]

Aftermath [edit]

President Jefferson Davis was captured and imprisoned on May x, 1865, marking the effective finish of the Confederate government. In addition, that day Usa President Andrew Johnson declared "armed resistance ...virtually at an stop."[22] Historian James McPherson joins other historians in concluding that the state of war concluded when the regime concluded.

Confederate Full general Edmund Kirby Smith officially surrendered all Confederate forces in the Trans-Mississippi Department on June two, 1865, except those under the command of Brigadier General Chief Stand Watie in the Indian Territory.[23] Stand Watie, of the 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles, on June 23, 1865, became the concluding Amalgamated general to surrender his forces, in Doaksville, Indian Territory.[24] On that same day, U.s. President Andrew Johnson ended the Union blockade of the Southern states.[25]

Many senior Amalgamated commanders in Texas (including Smith, Walker, Slaughter, and Ford) and many troops with their equipment fled across the border to United mexican states. Wanting to resist capture, they may also have intended to ally with French Purple forces, or with Mexican forces under deposed President Benito Juárez.

The Military Sectionalisation of the Southwest (after June 27 the Partition of the Gulf), allowable by Maj. Gen. Phillip H. Sheridan, occupied Texas between June and August. Consisting of the IV Corps, XIII Corps, the African-American XXV Corps, and 2 4,000-man cavalry divisions commanded by Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt and Maj. Gen. George A. Custer, it aggregated a l,000-man force on the Gulf Declension and along the Rio Grande to pressure the French intervention in Mexico and garrison the Reconstruction Department of Texas.

In July 1865, Barrett proffered charges of defiance of orders, fail of duty, abandoning his colors, and bear prejudicial to skillful lodge and military discipline against Morrison for deportment in the battle, resulting in the latter's courtroom martial. Confederate Col. Ford, who had returned from Mexico at the request of Union Gen. Frederick Steele to act every bit parole commissioner for disbanding Confederate forces, appeared as a defense witness and assisted in absolving Morrison of responsibility for the defeat at Palmito Ranch.[5]

The history of this date provides accounts of the roles of Hispanic Confederate veterans and of the handling by Confederates in South Texas of black prisoners-of-state of war. Hispanic Confederates served at Fort Dark-brown in Brownsville and on the field of Palmito Ranch. Col. Santos Benavides, who was the highest-ranking Hispanic in either regular army, led between 100 and 150 Hispanic soldiers in the Brownsville Campaign in May 1865.[26]

Some of the Sixty-2nd Colored Regiment were too taken [in the Boxing of Palmito Ranch]. They had been led to believe that if captured they would either exist shot or returned to slavery. They were agreeably surprised when they were paroled and permitted to depart with the white prisoners. Several of the prisoners were from Austin and vicinity. They were assured they would be treated as prisoners of state of war. In that location was no disposition to visit upon them a mean spirit of revenge.[27]

—Colonel John Salmon Ford, May 1865

When Colonel Ford surrendered his command following the campaign of Palmito Ranch, he urged his men to honor their paroles. He insisted that "The negro had a correct to vote."[27]

"Last battle of the Civil War" [edit]

Although officially almost historians say this was the last state action fought between the North and the South, some sources suggest that the battle on May 19, 1865, of Hobdy's Bridge, located nearly Eufaula, Alabama, was the last skirmish between the two forces. Wedlock records show that the concluding Northern soldier killed in combat during the war was Corporal John W. Skinner in this activity. Iii others were wounded, besides from the aforementioned unit of measurement, Company C, 1st Florida U.S. Cavalry.[28] [29]

Historian Richard Gardiner stated in 2013 that on May 10, 1865:

- A confrontation took place at Palmetto Ranch. There was no Confederacy in existence when the "battle" occurred. The ex-Confederates at Palmetto Ranch were aware that Lee had surrendered and that the war was over. What happened in Texas tin can merely be understood as a "post-state of war" encounter betwixt Federals and ex-Confederate "outlaws."[22]

The Confederates won this engagement, but every bit at that place was no organized command structure, there has been controversy almost the Marriage casualties. In 1896 these same men had their pensions cutting, although this was quickly rectified by an entreatment to the commissioner of pensions. The banana secretarial assistant to the commissioner overturned the alimony cut, legally ruling the men as the last Union casualties of the war.[28]

On April ii, 1866, President Johnson alleged the insurrection at an end, except in Texas. At that place a technicality apropos incomplete formation of a new state authorities prevented declaring the insurrection over.[24] Johnson declared the insurrection at an terminate in Texas and throughout the United States on Baronial 20, 1866.[24]

Battlefield [edit]

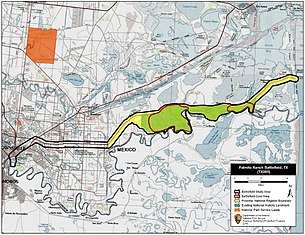

| Palmito Ranch Battlefield | |

| U.South. National Register of Celebrated Places | |

| U.South. National Celebrated Landmark | |

| Palmito Ranch Battlefield Show map of Texas Palmito Ranch Battlefield Prove map of the U.s. | |

| Nearest city | Brownsville, Texas |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 25°56′48″N 97°17′seven″Westward / 25.94667°N 97.28528°Due west / 25.94667; -97.28528 Coordinates: 25°56′48″N 97°17′vii″W / 25.94667°North 97.28528°Due west / 25.94667; -97.28528 |

| Area | 6,000 acres (two,400 ha) |

| NRHP referenceNo. | 93000266[30] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | June 23, 1993 |

| Designated NHL | September 25, 1997[31] |

The area has remained relatively unchanged, with the marshy, windswept prairies almost the same as they were in 1865. The site is more five,400 acres (2,200 ha) in size, and was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1997. The area is indicated by a large highway marker telling the history of the engagement, installed on the "Boca Chica Highway" (Texas Pike four) nigh where Palmito Ranch originally stood. The Civil War Trust (a division of the American Battlefield Trust) and its partners accept caused and preserved 3 acres (0.012 km2) of the battlefield.[32]

Panorama of the battleground

See also [edit]

- Listing of National Celebrated Landmarks in Texas

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Cameron Canton, Texas

Notes [edit]

- ^ Comtois, p. 51

- ^ a b Marvel, p. 69

- ^ Hunt, 2002, p. 32

- ^ Trudeau, 1994, p. 301

- ^ a b c "Historical Landmarks of Brownsville (Number 47)". University of Texas Brownsville. Archived from the original on April 17, 2006. Retrieved Apr 29, 2010.

- ^ Hunt, Jeffrey William (2002). The Final Boxing of the Civil War: Palmetto Ranch, p. 46. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-73460-three

- ^ Jerry Thompson, in Southwestern Historical Quarterly 107#2 (2003) pp. 336-337.

- ^ Texas State Historical Association

- ^ Kurtz, p. 32

- ^ Branson, David. "No. 2". The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official records of the Matrimony and Confederate Armies. Cornell University Library. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ Marvel, p. lxx. Fully 25% of the 34th was ill with fever and some other 25% detailed to labor duties.

- ^ a b Kurtz, p. 33

- ^ Comtais, p. 53

- ^ Trudeau, 1994, pp. 308–309

- ^ Marvel, p. 73

- ^ Official Records Function 1, Volume 48, pp. 265–267. He also claimed to accept written a study on the battle on May 18, 1865 just stated that "it may non have reached" higher headquarters.

- ^ Marvel, pp. 72–73

- ^ Oates, Stephen B. (1987). Rip Ford'southward Texas (Personal Narratives of the West), University of Texas Printing. ISBN 0-292-77034-0, p. 392

- ^ Thompson, Jerry, and Jones, Lawrence T. III (2004). Civil War and Revolution on the Rio Grande Frontier: A Narrative and Photographic History, Texas State Historical Association, ISBN 0-87611-201-seven, Note 78 p. 152

- ^ "Find a Grave". Find a Grave.

- ^ Marvel, p. 72

- ^ a b Richard Gardiner, "The Last Boxing?eld of the Civil War and Its Preservation," Journal of America'south Military Past (Spring/Summer 2013) vol 38 p9 online

- ^ Long, 1971, p. 692

- ^ a b c Long, 1971, p. 693

- ^ rev^6 "Long693"

- ^ Palmito Ranch, Battle of. Texas Historical Clan. Handbook of Texas Online, 2011

- ^ a b Ford, Salmon John. RIP Ford'due south Texas: Personal Narratives of the West. Edited by Stephen B. Oates. University of Texas Press. Austin, TX. (1987).

- ^ a b Hobdy'southward Span, Explore Southern History

- ^ Jaine Treadwell (May 9, 2015). "'Deadfall at Hobdy'due south Bridge' re-enactment May 16–17". The Troy Messenger. Retrieved July thirty, 2018.

Bob McLendon, event coordinator and fellow member of Pvt. Augustus Braddy Camp 385, an event sponsor, said ... on May 19, 1865 ... "Cpl. John West. Skinner of Commencement Florida Cavalry was killed and three Wedlock soldiers were wounded and were the terminal casualties of the war."

- ^ "National Register Information Arrangement – (#93000266)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ Staff (June 2011). "National Historic Landmarks Program: Listing of National Historic Landmarks by State, Texas" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved January ten, 2018. .

- ^ [1] American Battlefield Trust "Saved Land" webpage. Accessed May 25, 2018.

References [edit]

- Theodore Barrett'due south and David Branson's Official Battle Reports, pp. 265–269, Digital Library, Cornell University

- Bailey, Anne, J. Trans-Mississippi Department. p. 1100

- Benedict, H. Y. Texas In The Encyclopedia Americana. New York: The Encyclopedia Americana Corporation, 1920 OCLC 7308909

- Blair, Jayne E. The Essential Civil War: A Handbook to the Battles, Armies, Navies and Commanders. Jefferson, NC and London: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2006. ISBN 978-0-7864-2472-6

- Catton, Bruce. The Centennial History of the Civil War. Vol. 3, Never Call Retreat. Garden Metropolis, NY: Doubleday, 1965. ISBN 978-0-671-46990-0

- Comtois, Pierre. "State of war's Last Battle." America's Civil War, July 1992 (Vol. 5, No. 2)

- Conyer, Luther. Last Boxing of the War. From the Dallas, Texas News, Dec 1896. In Brock, R. A. Southern Historical Lodge Papers. Volume XXIV. Richmond: Published past the Guild, 1896 OCLC 36141719

- Civil War Trust web site. Retrieved January 20, 2014

- Civil War Preservation Trust. Campi, James, ed. and Mary Goundrey, Wendy Valentine. Ceremonious War Sites: The Official Guide to the Civil War Discovery Trail, 2d ed. Guilford, CT: The Globe Pequot Printing, 2008. ISBN 978-0-7627-4435-0. Start edition published 2003

- Delaney, Norman C. Palmito Ranch, Tex., eng. at. May 12–thirteen, 1865. p. 556. In Historical Times Illustrated History of the Civil War, edited by Patricia 50. Faust. New York: Harper & Row, 1986. ISBN 978-0-06-273116-6

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Armed services History of the Civil State of war. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5. Retrieved January 20, 2014

- "Manuscript: Letter by John Salmon "Rip" Ford describing the terminal battle of the Civil War". The Littlejohn Collection on Flickr. Wofford College, Sandor Teszler Library. November 6, 2008. Retrieved Dec 12, 2008.

- Forgie, George B. Brownsville, Texas: City of Brownsville In Current, Richard Due north. ed. The Confederacy: Selections from the Four-Volume Macmillan Encyclopedia of the Confederacy New York: Simon & Schuster Macmillan, 1993, introductory cloth, 1998. ISBN 978-0-02-864920-7. p. 173

- Frazier, Donald Southward. Brownsville, Texas: Battles of Brownsville. p. 173

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil State of war: A Narrative. Vol. 3, Scarlet River to Appomattox. New York: Random Business firm, 1974. ISBN 978-0-394-46512-8

- Gillett, Mary C. (US Army). The Ground forces Medical Department, 1818–1865. Washington, DC: Eye of Armed forces History, U.S. Regular army, 1987 OCLC 15550997 Retrieved January 18, 2014

- Glatthaar, Joseph T. The American Civil War: The War in the West 1863 – May 1865. Taylor & Francis, 2003. ISBN 978-1-57958-377-four. Starting time published: Oxford: Osprey, 2001. ISBN 978-ane-84176-242-5. Retrieved Jan 20, 2014

- Greeley, Horace. The American conflict: a history of the great rebellion in the The states. Book Two. Hartford: O.D. Case and Visitor, 1867. OCLC 84501265. Retrieved April ix, 2011. ISBN 978-0-8371-1438-five

- Hendrickson, Robert. The Road to Appomattox. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2000. ISBN 978-0-471-14884-five, p. 221.

- Hunt, Jeffrey Wm. The Terminal Boxing of the Civil War: Palmetto Ranch. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-292-73461-6, a scholarly history

- Hunt, Jeffrey Wm. Palmito Ranch, Battle of Handbook of Texas Online (1999)

- Jones, Terry 50. Historical Dictionary of the Civil State of war, Volume 1. Lanham, Doc: Scarecrow Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0-8108-7811-ii. Retrieved January xx, 2014

- Keegan, John. The American Civil War: A Military History. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, 2009. ISBN 978-0-307-26343-8

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. The Civil State of war Battleground Guide. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5

- Kurtz, Henry I. "Last Battle of the War." Civil State of war Times Illustrated, Apr 1962 (Vol. I, No. 1)

- Long, East. B. The Ceremonious War Mean solar day past Day: An Almanac, 1861–1865. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1971 OCLC 68283123 Page numbers are from 1971 print edition; web accost is for 2012 reprint.

- Lossing, Benson John and William Barritt. Pictorial history of the civil war in the United States of America, Volume three OCLC 1007582 Hartford: Thomas Belknap, 1877. Retrieved May i, 2011.

- Martin, ed., John H. Columbus, Geo., from Its Selection as a "trading Boondocks" in 1827, to Its Partial Devastation past Wilson'due south Raid in 1865.. Columbus, GA: Gilbert, Book Printer and Binder, 1874. p. 178

- Marvel, William. Battle of Palmetto Ranch: American Ceremonious War's Final Battle. Originally published past Civil War Times mag equally "Last Hurrah at Palmetto Ranch", January 2006 (Vol. XLIV, No. 6). Published Online: June 12, 2006. Retrieved from Historynet.com on January twenty, 2014

- Pollard, Edward A. The Lost Cause; A New Southern History of the State of war of the Confederates. New York: E. B. Care for & Co. 1867 OCLC 18831911

- Studies in History, Economics, and Public Constabulary, Volume 36. New York: Columbia University Press, 1910, p. 26 OCLC 6342393

- Swanson, Marker. Atlas of the Civil War, Month past Month: Major Battles and Troop Movements. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-8203-2658-0. Retrieved January 17, 2014

- Tucker, Phillip Thomas. The Final Fury: Palmito Ranch, The Last Battle of the Civil State of war (2001), a scholarly history

- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. Almanac of American Military History, Volume 1. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2012. ISBN 978-1-59884-530-iii. Retrieved Jan 20, 2014

- Trudeau, Noah Andre. Like Men of War: Black Troops in the Civil War 1862–1865. Edison, NJ: Castle Books, 2002. ISBN 978-0-7858-1476-4. Originally published: New York: Fiddling, Brownish and Visitor, 1998

- Trudeau, Noah Andre. Out of the Storm: The End of the Civil War, April – June 1865. Boston: Trivial, Brown & Company, 1994. ISBN 0-316-85328-iii

- "Battle of Palmito Ranch", U.South. National Park Service; CWSAC Battle Summaries. Retrieved Jan 20, 2014

- Wagner, Margaret Eastward., Gary W. Gallagher,Hayden L Gomez, and Paul Dicklemen. The Library of Congress Ceremonious State of war Desk Reference. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, Inc., 2009 edition. ISBN 978-1-4391-4884-6. First Published 2002. pp. 328–330

- Ward, Geoffrey C. and Kenneth Burns. The Civil War. New York: Knopf, 1990, p. 317. ISBN 978-0-394-56285-8. Retrieved January 17, 2014

- Wertz, Jay and Edwin C. Bearss. Smithsonian's Great Battles and Battlefields of the Civil State of war. New York: William Morrow & Co., 1997. ISBN 978-0-688-13549-2

External links [edit]

- A PDF of Fish and Wild animals Service Information on the Park and Battle

- PDF on Texas Historic Civil State of war Battlefields

Battle Of Palmito Ranch Date,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Palmito_Ranch

Posted by: dentoncorties.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Battle Of Palmito Ranch Date"

Post a Comment